From Chaos to Order: The Eigenstate Thermalisation Hypothesis

This article explains how quantum systems can appear to reach thermal equilibrium, even though their evolution is fully reversible and depends on initial conditions. It introduces the Eigenstate Thermalisation Hypothesis (ETH), which suggests that the behavior of small parts of large quantum systems becomes independent of their initial state due to interactions with the rest of the system. Through simple spin models and numerical examples, the article shows how increasing the number of particles leads to thermal-like behavior. It is intended for undergraduate physics students familiar with basic quantum mechanics and thermodynamics.

Date: 22 September, 2024

Category: Physics

Table of Contents

- Can Quantum Systems Thermalise?

- The Eigenstate Thermalisation Hypothesis

- Quantum Thermalisation in Action

- Looking Beyond

- References

Thermalisation in Classical Systems: Irreversability and Role of Temperature

If we place a large number of oxygen molecules in a corner of an isolated box and wait for some time, what would be the final distribution of the speeds of the molecules? The answer is, to a very good approximation, the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution function:

where is the mass of each molecule, is the Boltzmann constant and is the temperature of the system, fixed by the total energy through the equipartition theorem . This is one example of the power of statistical thermodynamics: given only the macroscopic parameter , it allows the calculation of average quantities to very high accuracies. This experiment is shown in Fig. 1.

It is useful to examine some qualitative features of this solutions:

- The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution is independent of the initial conditions, except through the total energy . No matter how the molecules are initially setup, time evolution ensures that they end up in the same distribution.

- The time evolution is irreversible. Even if all the molecules start out with identical speeds, they will almost certainly end up with speeds that are distributed at differing values, according to the above-mentioned distribution.

FIG 1. Molecules kept at the corner of a box in an orderly fashion results in their speeds getting distributed according the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution (right panel).

Within the formulation of statistical mechanics, they are explained using the ergodic hypothesis: given enough time, each molecule explores the entirety of its available phase space, and in doing so, the measured value is equal to the average within the patch of phase space at the appropriate energy 1 2.

Can Quantum Systems Thermalise?

While this explanation makes sense from a classical standpoint, it is hugely problematic for quantum evolution. Given a system of particles with a many-particle wavefunction described by a Hamiltonian , the state of the system a later time is given by (setting to 1)

Both of the qualitative features mentioned in the previous section are absent in quantum time evolution: the evolution is time-reversible, and the final state depends on the details of the initial state . This is easily demonstrated by a simple model.

FIG 2. Systems of two spins. The interact with each other through spin-flip processes.

Consider two spins interacting with each other through simultaneous flips; if one flips down, the other must flip up, and vice versa (Fig. 2). The operator for an up(down) flip is , so the Hamiltonian describing this process is

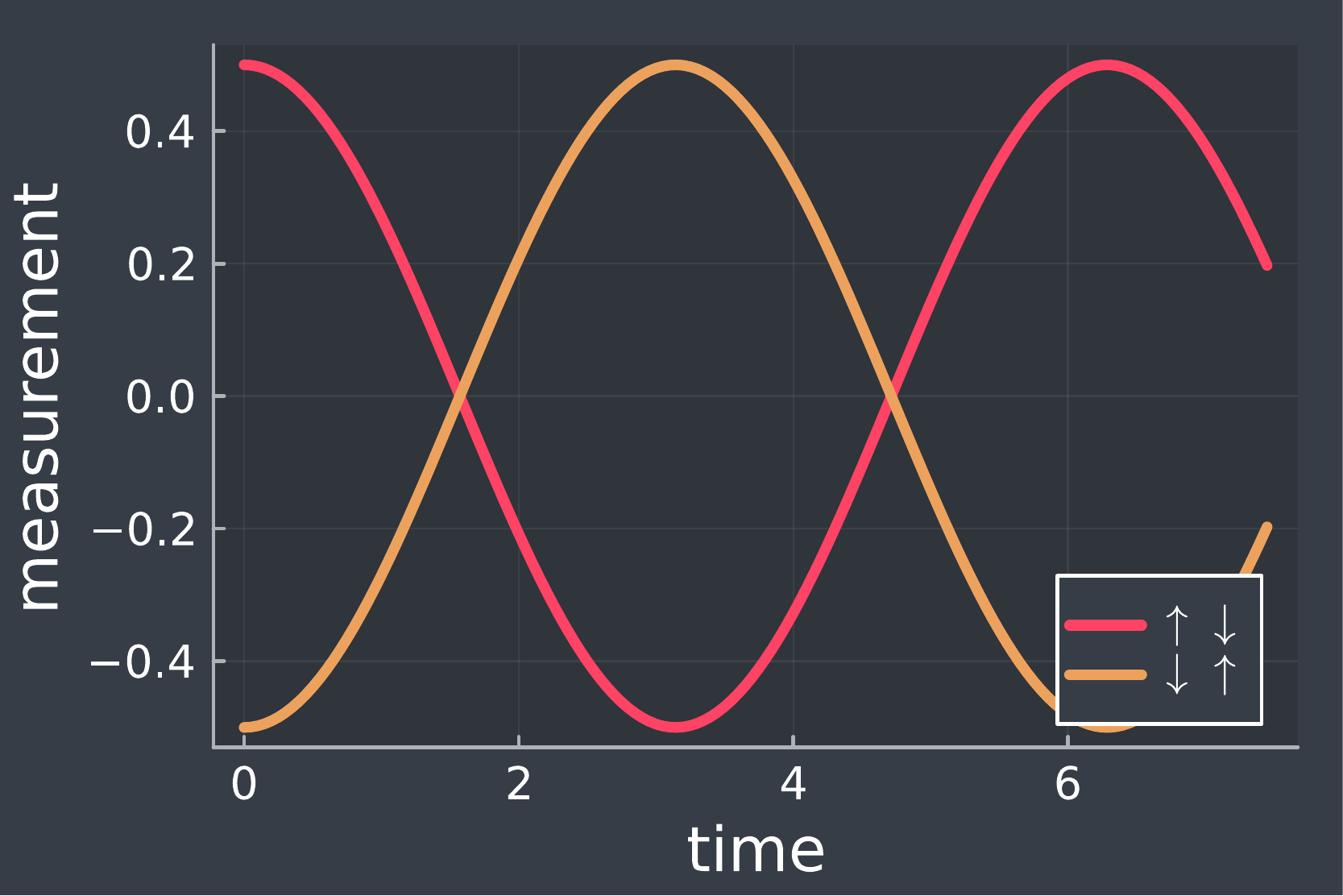

The first term flips the first spin up and the second spin down, while the second term does the opposite. We perform two parallel time evolution calculations, one with the initial state (red curve in Fig. 3), and another with the initial state (orange curve). For both the cases, we calculate the time evolution of the component of the first spin, defined as , being the component of the first spin. The results are shown in Fig. 3, and we can draw the following conclusions:

- The time evolution does depend on initial conditions. The curve that starts from the state does not in general match with the curve that starts from the state.

- The evolution is reversible; the initial values are recovered at every time step. This reversibility is also encoded in the fact that the evolution is unitary and all information is preserved in the process.

The challenge then is the following: If we expect our universe to be fundamentally quantum, how do we reconcile these two features with those of thermalization (described above). More specifically, how can unitary quantum evolution lead to a thermal state that has no memory of the initial state and that is in accordance with the predictions of thermodynamics?

FIG 3. Time evolution the average spin along direction for the first spin. The red curve is for an initial state where the first spin is up and the second one is down, while the orange curve starts with a flipped initial state. The evolution is obtained by applying the time evolution operator on the initial state.

The Eigenstate Thermalisation Hypothesis

In the late twentieth century, the eigenstate thermalisation hypothesis (ETH) was proposed as a solution to the above question 3 4. It is an ansatz for the matrix elements of operators in the eigenbasis of the Hamiltonian:

The ansatz certainly looks more intimdating than it is; it says that given an observable that can be measured in a laboratory, its matrix elements in the eigenbasis of the Hamiltonian is equal to the microcanonical expectation value at the average energy if , and it obtains corrections that are exponentially suppressed by the entropy . Since is extensive, these corrections vanish in the thermodynamic limit . Such an ansatz of course immediately explains the thermal behaviour of statistical mechanics, almost as a matter of principle, because in any eigenstate of the system at energy , the expectation value of the operator will be, to a very good approximation, , which is the expected value.

More importantly, we should analyse what this means for the mechanism of thermalisation in quantum systems. The ETH tells us that quantum systems thermalise locally; even though the evolution of the total system is reversible and dependent on the initial conditions, the temporal behaviour of any small subsystem (a single particle, a single point in space, etc) becomes incoherent very fast. This happens because the information of the initial configuration of any individual particle gets scrambled through interactions with a macroscopic number of particles. This also explains the title of the article: multiple initial states (chaos) lead to the same value of the local observable (order) 5.

Quantum Thermalisation in Action

FIG 4. Model of several interacting spins. Each spin interacts with the two spins on each side of itself, through coordinated spin-flips.

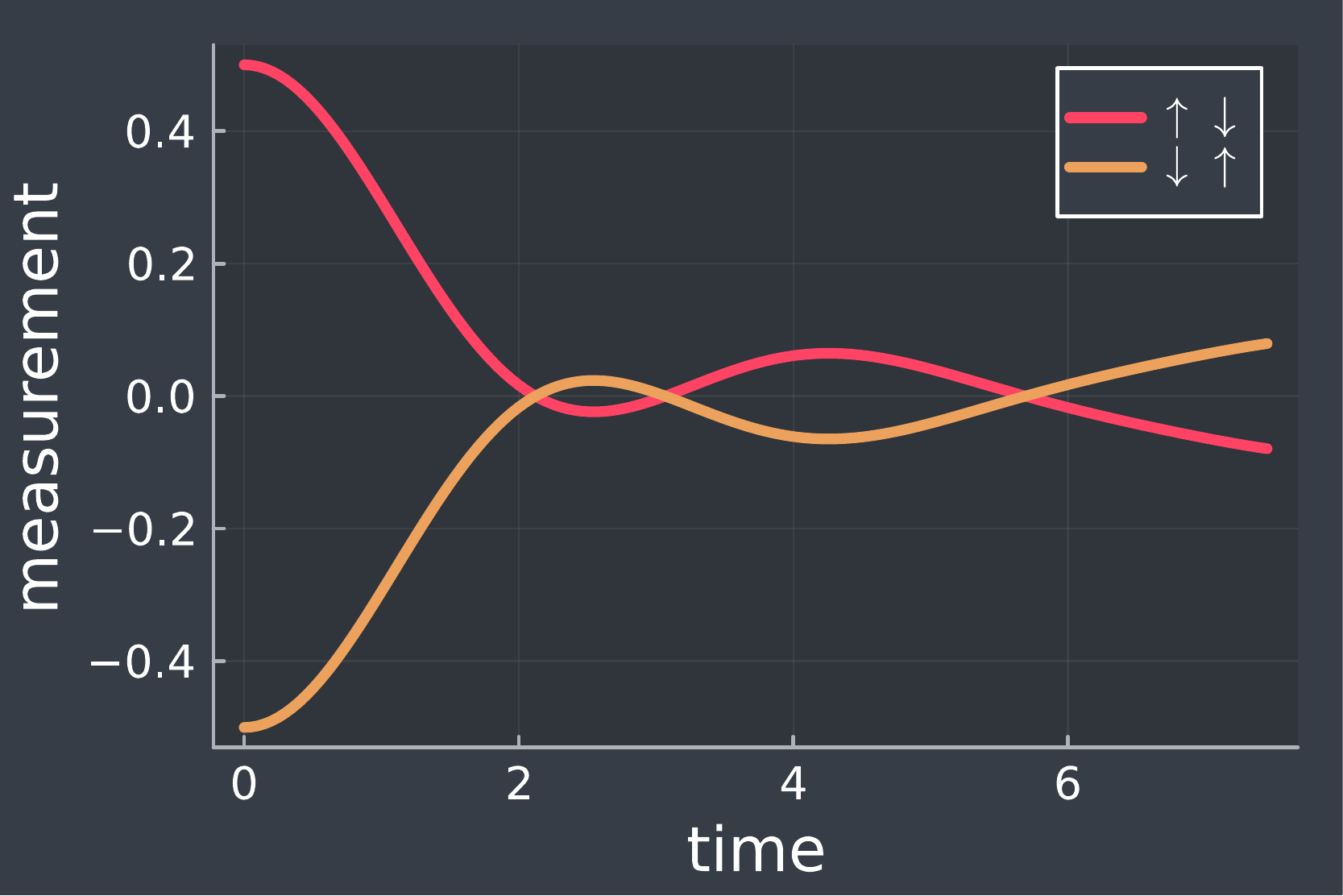

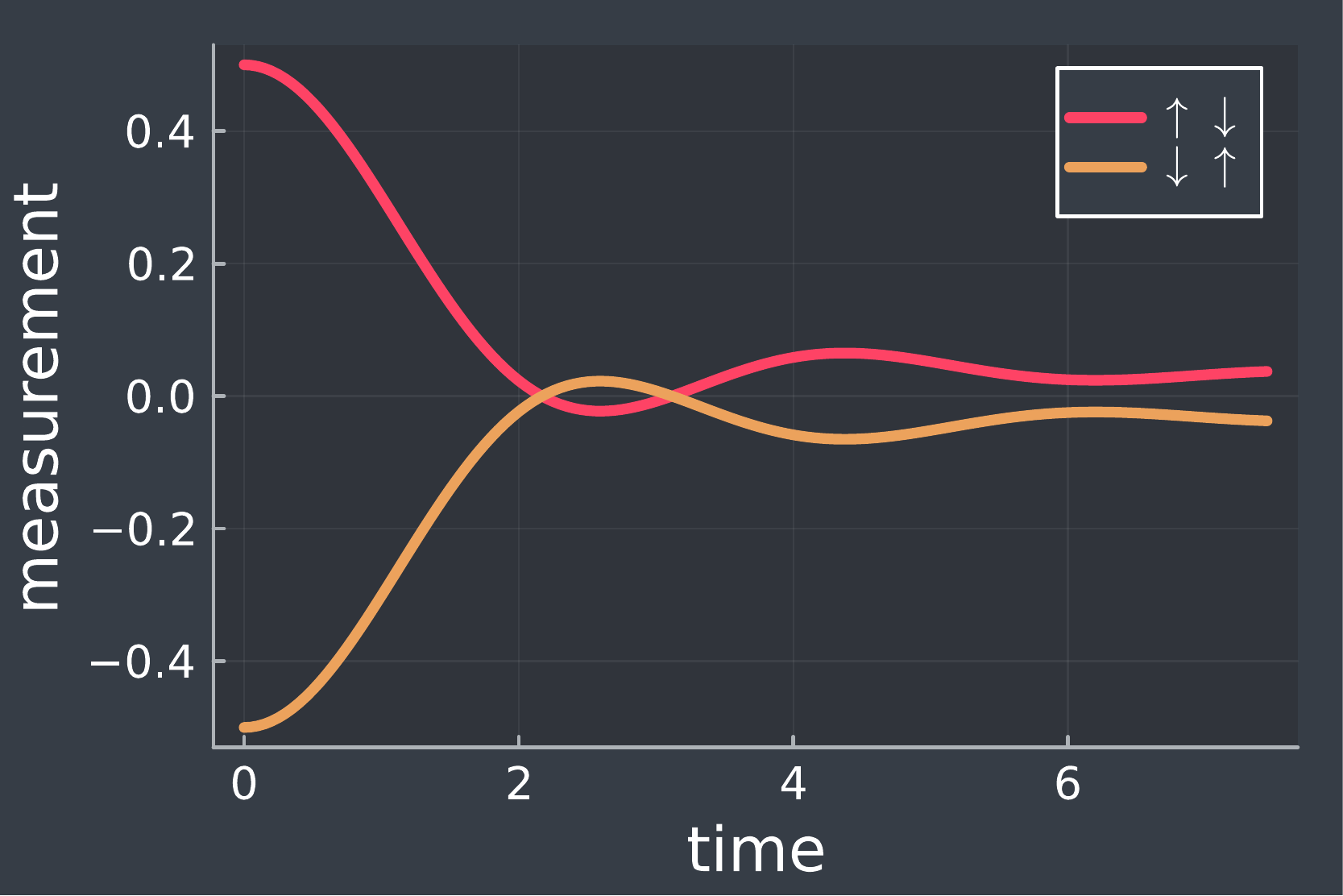

The upshot of the previous section was that quantum systems thermalise through interactions with other particles. This also explains why we did not see thermalisation in Fig. 3 - there weren’t enough interacting spins present to allow local information to scramble! To see the emergence of information scrambling as the number of spins are increased, we perform the same computations but now for and spins, for similar kind of Hamiltonians (each spin interacts with its neighbouring spins through spin-flips). The model is shown in Fig. 4.

The results are shown in Fig. 5, and effect of increasing number of spins is quite apparent! Compared to the case of (shown in Fig. 3), the long-time evolution of both the initial states are approaching similar values, and the effect is more pronounced for than for . This demonstrates how local measurements on a many-particle system display the loss of initial state memory (both the initial states approach similar values as ) as well as the emergence of irreversibility (the oscillations get suppressed).

FIG 5. Evolution of expectation value of component of first spin for spins and spins. As is increased, the values better thermalise to common values.

Looking Beyond

It should now be clear from the above discussion that the thermalisation we see around us (and that are in agreement with statistical thermodynamics) likely results, more fundamentally, from the quantum interactions between system and universe. This is expressed formally by the ETH, and demonstrated in Fig. 5. While there is yet no derivation of the ETH, it has been tested on various systems and has proven to be quite successful. Heuristic justifications of the ETH come from random matrix theory (RMT): it can be proved that eigenvectors of random matrices satisfy an equation similar to ETH, and the leap from RMT to quantum mechanics is then made by saying that interacting systems of a large number of particles are sufficiently complicated so as to be well-represented by random matrices. On the frontier, research is being carried out on exotic systems that violate the hypothesis (and hence the predictions of statistical mechanics) 6. People are also looking into fundamental open questions such as the relation between ETH and entanglement.

References

-

“A. P. Luca D’Alessio, Yariv Kafri and M. Rigol, From quantum chaos and eigenstate thermalization to statistical mechanics and thermodynamics, Advances in Physics 65, 239 (2016).” ↩

-

“J. M. Deutsch, Eigenstate thermalization hypothesis, Reports on Progress in Physics 81, 082001 (2018).” ↩

-

“M. Srednicki, Chaos and quantum thermalization, Phys. Rev. E 50, 888 (1994).” ↩

-

“J. M. Deutsch, Quantum statistical mechanics in a closed system, Phys. Rev. A 43, 2046 (1991).” ↩

-

“M. Rigol, V. Dunjko, and M. Olshanii, Thermalization and its mechanism for generic isolated quantum systems, Nature 452, 854 (2008).” ↩

-

“S. Sinha, S. Ray, and S. Sinha, Classical route to ergodicity and scarring in collective quantum systems, Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 36, 163001 (2024).” ↩